The positive effects of the human-animal bond are undeniable, but how exactly do they come about? While research and anecdotes have demonstrated that animal-assisted interventions are effective, Andrea M. Beetz delves into theories about why and how they are effective in her 2017 article, “Theories and possible processes of animal assisted interventions.” Here, we’ll examine possible mechanisms of action for AAI, as well as Beetz’s indications for further research in this field.

E.O. Wilson, an American biologist and Harvard Professor of Entomology, is responsible for the concept of biophilia:

E.O. Wilson, an American biologist and Harvard Professor of Entomology, is responsible for the concept of biophilia:

“Wilson coined the term ‘biophilia’ to describe what he believes is an innate human affinity with other forms of life. It is innate because our culture and behaviour are partially encoded in our genes, and it has been sustained throughout evolution because human life and death have always depended primarily upon our fellow creature…[p]ut simply, we are hard-wired to be interested in living things” (Merrick, 2014).

Wilson’s term is supported by research that found that infants and children are more drawn to animals than to inanimate objects. It is also grounded in history; humans have always lived around animals or been dependent upon animals for survival. Not only have they long been used as a source of food, they also offer indication of nearby threats. Humans learned that calm animals were an indication of a safe environment, known as “the biophilia effect.” The biophilia effect supports the idea that clients can be relaxed by the presence of calm animals during AAI.

Beetz explains that anthropomorphism is frequently seen as “an undesirable tendency of humans to treat companion animals similarly to humans,” including dressing them up in clothes and assuming that they enjoy the activities that their human counterparts enjoy. However, anthropomorphism can also be spun positively, as a type of empathy that allows us to understand the needs, behaviors, and intentions of animals. The closer the genetic makeup of the animal to a human, the easier it is to anthropomorphize with that animal. For example, dogs (which make up the majority of animals who provide AAI) are social mammals like humans, which makes it easier for us to ascribe complex mental states to them than, say, snakes. This ability to empathize with therapy animals may explain why animal-assisted interventions work.

Beetz explains that anthropomorphism is frequently seen as “an undesirable tendency of humans to treat companion animals similarly to humans,” including dressing them up in clothes and assuming that they enjoy the activities that their human counterparts enjoy. However, anthropomorphism can also be spun positively, as a type of empathy that allows us to understand the needs, behaviors, and intentions of animals. The closer the genetic makeup of the animal to a human, the easier it is to anthropomorphize with that animal. For example, dogs (which make up the majority of animals who provide AAI) are social mammals like humans, which makes it easier for us to ascribe complex mental states to them than, say, snakes. This ability to empathize with therapy animals may explain why animal-assisted interventions work.

Anthropomorphism may be helpful in building social relationships with animals, but caution also needs to be taken. It is often responsible for the misinterpretation of canine facial expressions and body language. All in all, anthropomorphism is an interesting theory for the success of AAI through the basis of meaningful interactions with animals.

“The experiential system processes the experiences of the real world directly—the sounds, smells, pictures, touch, overall sensory input, while via the verbal-symbolic system reality is experienced indirectly through words and symbols.”

“The experiential system processes the experiences of the real world directly—the sounds, smells, pictures, touch, overall sensory input, while via the verbal-symbolic system reality is experienced indirectly through words and symbols.”

How do these methods of processing information relate to animal-assisted interventions? When we interact with animals, it’s likely that the experiential system, the system more closely connected to subconscious thought and emotion, is at work. This system of functioning is rooted more deeply in human behavior, while the verbal-symbolic system represents conscious communication through verbal and digital means. Using this theory, we find that the experiential system is the main way we are able to communicate with animals on a more emotional, intuitive level, while with humans we are used to communicating mostly through verbal or written communication. The theory is that human–animal interaction helps balance these two ways of information processing, which leads to promotion of positive feelings, reduction of depression, and increased motivation.

The dual-systems approach in motivation theory describes the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation involves acting for one’s own satisfaction or enjoyment of an activity, while explicit motivation implies an outside reward or tangible outcome (positive or negative) for participating in a certain activity.

The dual-systems approach in motivation theory describes the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation involves acting for one’s own satisfaction or enjoyment of an activity, while explicit motivation implies an outside reward or tangible outcome (positive or negative) for participating in a certain activity.

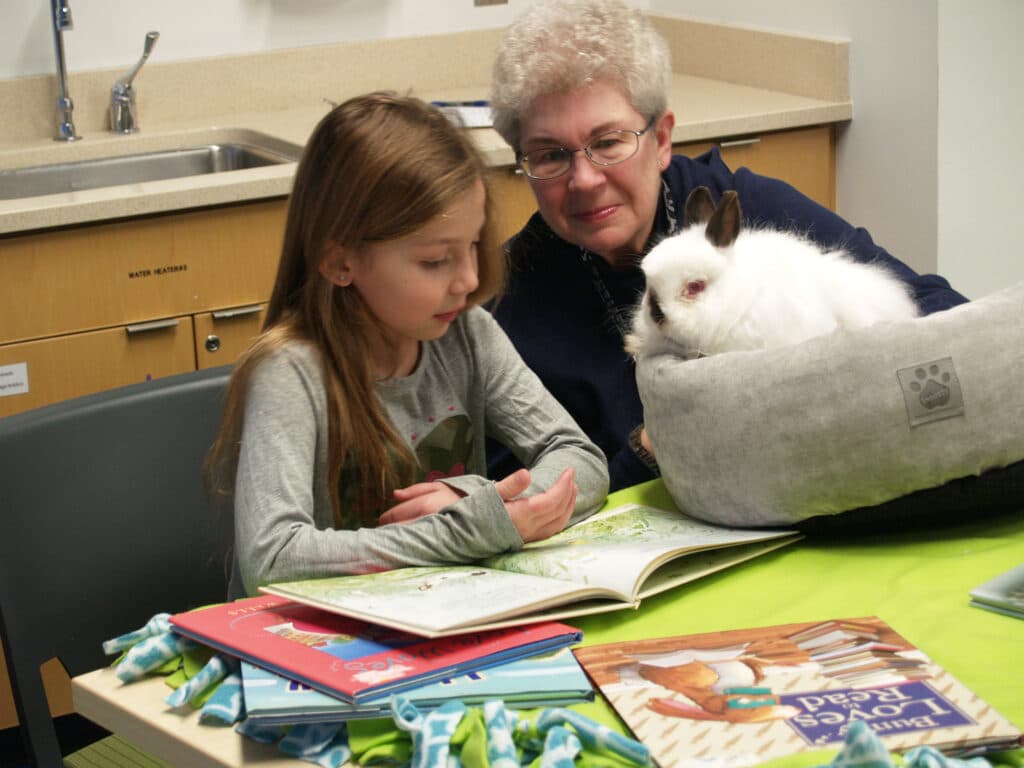

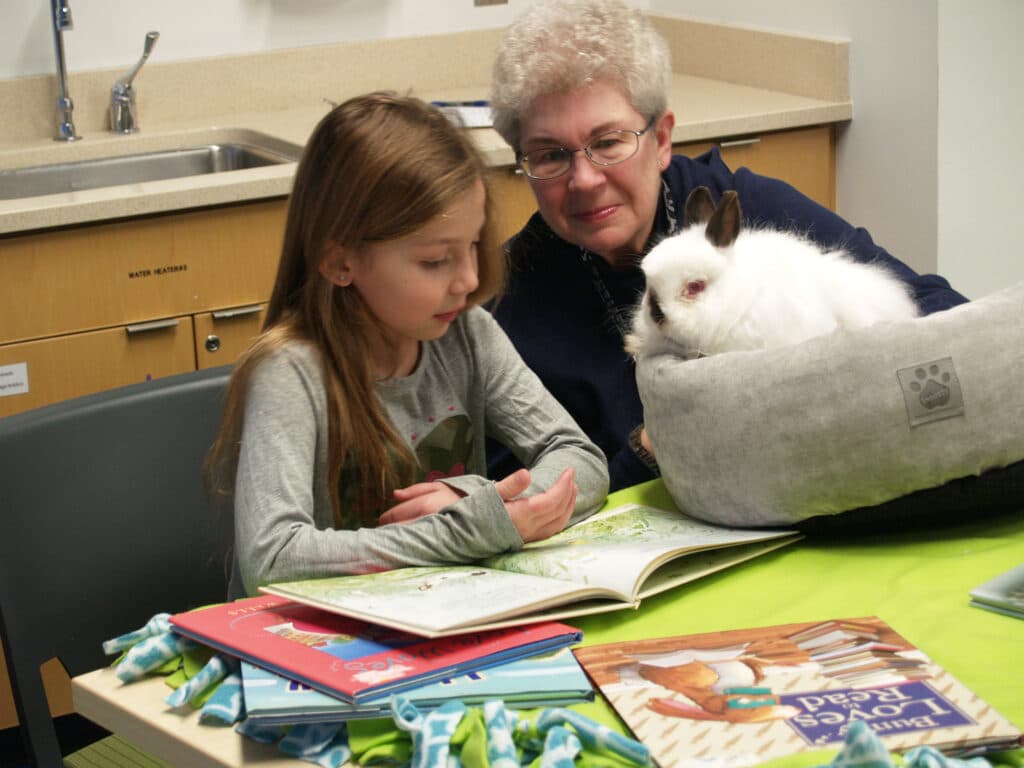

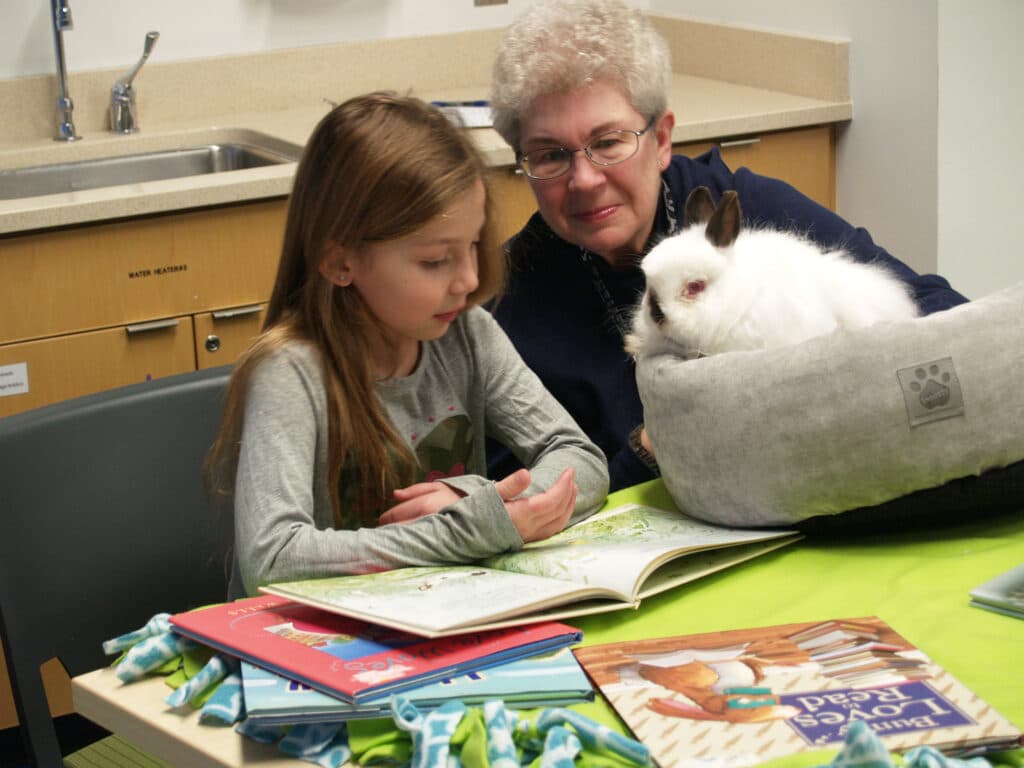

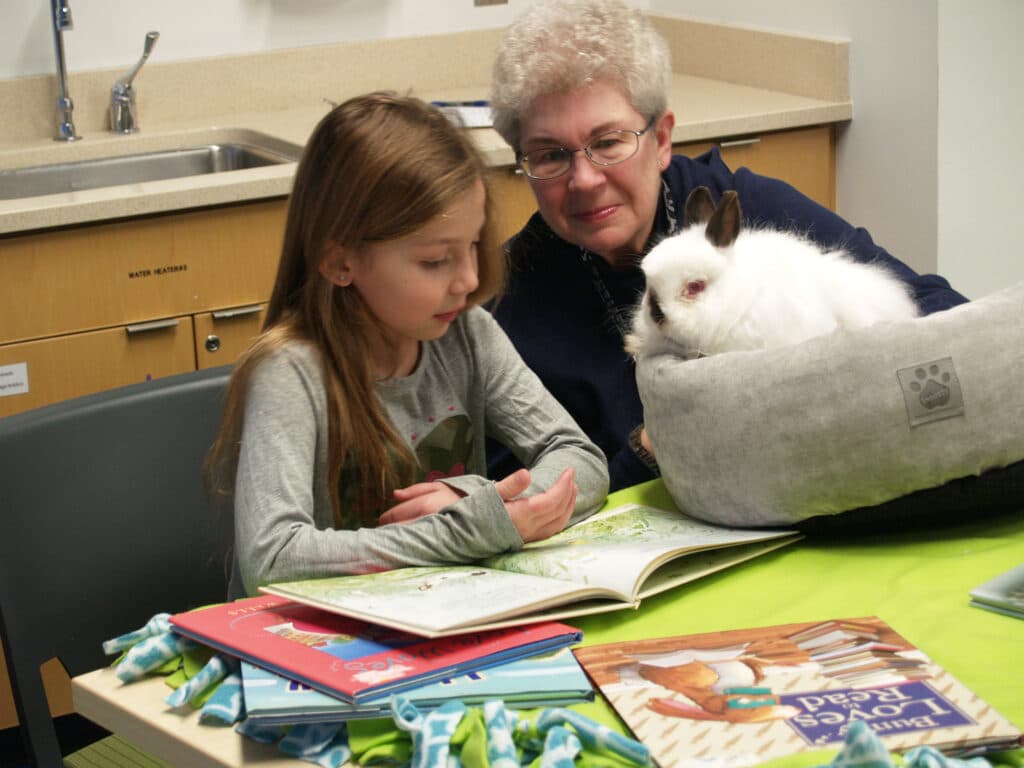

Intrinsic motivations are closely linked with the previously mentioned experiential system; they rely on innate enjoyment of a situation and are connected to nonverbal incentives. Unfortunately, many of the systems put in place in modern society rely on extrinsic motivation (grades, money, fear of negative feedback from a teacher or boss, and similar external influences.). Human–animal interactions, however, provide an opportunity for increasing intrinsic motivation and possibilities for success without fear of extrinsic consequences. Research has supported this theory in the realm of reading to dogs. Low reading comprehension has been linked to low intrinsic motivation for reading. However, dog-assisted reading programs have been shown to increase intrinsic motivation to participate in reading, leading to a possible increase in reading comprehension.

Activation of the oxytocin system is a key method of action in animal-assisted interventions. Oxytocin is a hormone and neurotransmitter that reduces anxiety, increases pain tolerance, and promotes communication, trust, and bonding. It’s released into the brain and circulatory system during pleasant physical contact and touch, a cornerstone of most AAI.

Activation of the oxytocin system is a key method of action in animal-assisted interventions. Oxytocin is a hormone and neurotransmitter that reduces anxiety, increases pain tolerance, and promotes communication, trust, and bonding. It’s released into the brain and circulatory system during pleasant physical contact and touch, a cornerstone of most AAI.

Research supports increases in oxytocin through interaction with animals, such as petting familiar and unfamiliar dogs (though oxytocin levels increase more when the dog is familiar), or even through mere eye contact with a dog. Animals are thought to have such a strong effect on individuals’ oxytocin levels, as opposed to interactions with other humans, because it is more socially appropriate to display public affection with an animal than with a human. Additionally, previous experiences with attachment figures may prevent oxytocin release during human-to-human interaction.

Regulation of stress and negative emotions through social support is another theory supporting mechanism of action for animal-assisted interventions. If children form secure attachments with their caregivers, they are able to more effectively manage stress and safely explore their environment. If they have insecure or disorganized attachment styles, they are less able to effectively regulate stress and negative emotions. Social support theories also relate to the regulation of stress through means including physical contact and emotional support.

Regulation of stress and negative emotions through social support is another theory supporting mechanism of action for animal-assisted interventions. If children form secure attachments with their caregivers, they are able to more effectively manage stress and safely explore their environment. If they have insecure or disorganized attachment styles, they are less able to effectively regulate stress and negative emotions. Social support theories also relate to the regulation of stress through means including physical contact and emotional support.

Most humans approach animals with a secure attachment, regardless of form of attachment to a caregiver. This may provide insight into how human–animal bonds can be more effective than human-to-human bonds in individuals that have insecure or disorganized attachment styles. Companion animals have also been found to be social supports for both children and adults during times of stress. Additionally, animals “are usually willing recipients of caregiving[…]successfully providing care to offspring is affiliated with positive emotions, stress reduction, and activation of the oxytocin system.” Therefore, individuals who care for a companion animal or therapy animal may experience effects similar to those of caring for one’s offspring.

Distraction from pain, anxiety, and negative mood is a benefit of animal-assisted therapies, as well as a mechanism of action. Anecdotal evidence supports this theory (see paws on pain [link]), but there is little actual research on the topic.

Beetz states, “[U]nderstanding these processes can also indicate the conditions that need to be met in order to gain the desired effects of AAI.” The more knowledge we have regarding the methods of action in AAI, the more effectively we can deliver interventions and change lives. As always within this field, more research is indicated to support these theories. However, Beetz allows us to have a great starting point on the road to understanding just how AAI works.

References